Let me take you back in time and away from here. The year is 1815 and we are on the island of Sumbawa in present-day Indonesia, then part of the Dutch East Indies. On 5th of April of that year, a major volcanic eruption took place at Mount Tambora, on the northern part of the island. This was the most powerful Volcanic eruption in recorded human history, with a Volcanic Explosivity Index of 7. Before the explosion, Mount Tambora’s peak elevation was about 4,300 meters, one of the tallest peaks in the region, but after the explosion it dropped to about two-thirds of its previous height. The explosion was heard 2,600 kilometers away, and ash fell at least 1,300 kilometres away.

All vegetation on the island was destroyed. Uprooted trees, mixed with pumice ash, washed into the sea and formed rafts up to 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) across. A moderate-sized tsunami struck the shores of various islands in the Indonesian archipelago with a height of up to 4 meters. In fact, although the eruption reached its violent climax within a few days, increased steaming and small eruptions occurred during the next six months to three years.

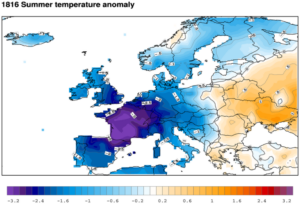

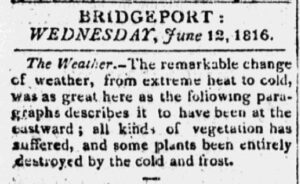

The consequences impacted a much wider area. The resulting ash from the eruption columns dispersed around the world and lowered global temperatures in an event sometimes known as the Year Without a Summer in 1816. This brief period of significant climate change triggered extreme weather and harvest failures in many areas around the world, most notably in Europe and North America. Crops were killed – either by frost or a lack of sunshine. This caused food to be scarce.

Regretfully, this very significant cooling directly or indirectly caused 90,000 fatalities.

A side effect of this famine was that the price of oats increased dramatically. As a result, tens of thousands of horses starved to death, and many more were slaughtered either to save money or to become a dinner. The shortage of oats was thus akin to a modern fuel crisis, and by early 1817 transport and industry in Germany was grinding to a halt.

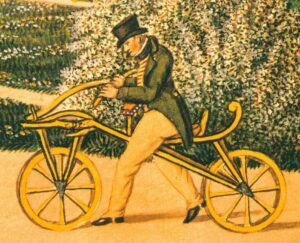

Apparently, this prompted Karl Freiherr von Drais, a noble German forest official and prolific inventor, to consider an alternative transportation method, to replace horses.

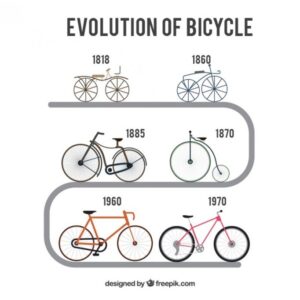

Drais conceived a two-wheeler without pedals, that was the earliest form of a bicycle. It was initially called Laufmaschine (“running machine”), and later called the velocipede, or – after its inventor – draisine (English) or draisienne (French).

The first reported ride from Mannheim to the “Schwetzinger Relaishaus” (a coaching inn, located in “Rheinau”, today a district of Mannheim) took place on 12 June 1817. Karl rode his bike to a distance of about 7 kilometers and the round trip took a little more than an hour.

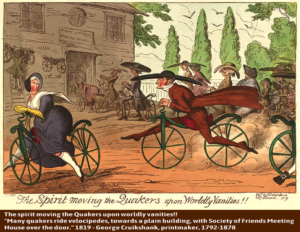

But Karl didn’t have an easy life as an entrepreneur. He was unable to market his inventions for profit because he was still a civil servant of Baden. Additionally, the wider adoption of the new technology was delayed due to safety concerns (sounds familiar?): it soon became evident that the carriages made the roads so bumpy that it was impractical to ride the velocipede on such roads, so users took to the pavements moving far too quickly and putting pedestrians’ safety at risk. Consequently, authorities in Germany, Great Britain, the United States, and even Calcutta banned its use, stalling the further development of bicycles for a few decades

Be it as it may, this was the beginning of horse-less transportation options, that led to future generations of more advanced bicycles, and eventually motorbikes (1885) and cars (1886).

=====================================

I used this story as my opening comments at a recent on-line meetup Veriest organized – to set the stage for an exchange of ideas, knowledge sharing and to motive the audience to collectively look for ways to do things differently and better.

In my view, there are many parallels between the events in the aftermath of Mount Tambora’s eruption and the COVID-19 period we’re living in. True, we’re experiencing a “silent disaster”: an alien visiting our cities today would not understand why they are that empty and quiet as there are no major climatic or other “physical” evidence of a major catastrophe, unlike a volcanic eruption, hurricane, flood or other similar natural disasters. Still, we’re undergoing a major disruptive moment in human history that poses first of all life-threatening conditions to people as well as major changes to how we live our lives.

Today, as in those days in the 18th century, some good and important efforts are being invested in making sure the “horses can continue to run”. People and organizations are trying their best to continue their “normal business” and resume their daily routines, as “the show must go on”. But as we all know, for many this is not that easy, and people are looking for what will be the “new normal”.

There are indeed signs of disruptive creativity, as companies come-up with innovative solutions out of necessity. They are re-assessing their old assumptions about how to conduct their business, how to interact with employees and customers without face to face meetings, how to restructure their supply chains, and how to re-engineer their processes.

We may all need to look for what horses will be replaced and what new bicycles need to be invented during and in the aftermath of this pandemic.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1815_eruption_of_Mount_Tambora

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2016/10/25/year-without-summer/